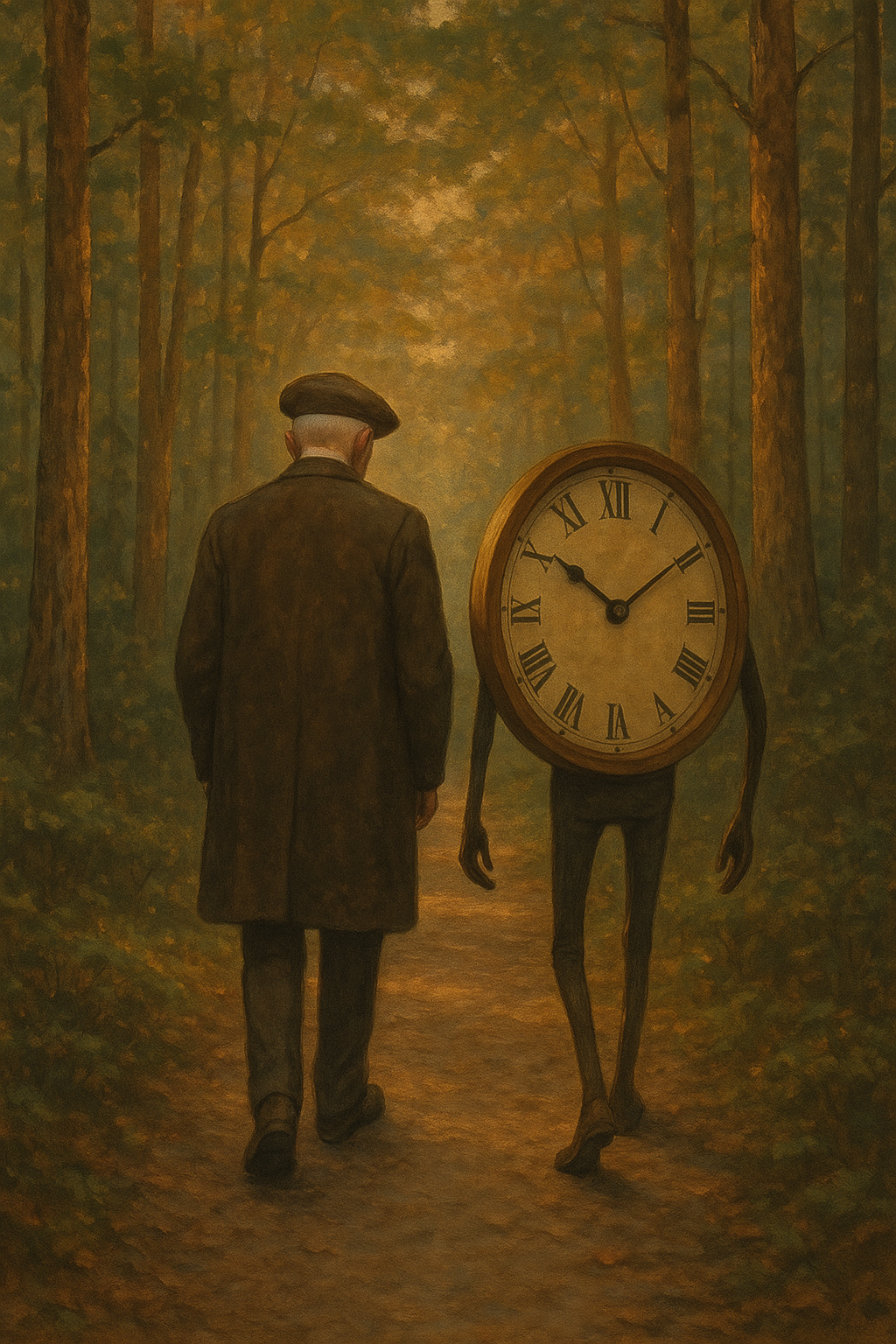

I help time know what it is

Walking heightens awareness of time. Time isn't just an abstract idea. It is practical, experienced, and felt.

Also published on my Substack, Wombat Safari

“I help time know what it is, just as time knows what I will become.”

Terry Pratchett, Dodger

Time as mystery

Augustine once asked, “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain it to one who asks, I know not.”

We break time into hours and seasons, measure it with watches and calendars, but these convenient tools we overlay onto something much stranger. Our obsessive measurement of time helps us understand what it is: we give it names, boundaries, and rhythms it doesn’t have on its own.

But time also knows what I will become. The future, hidden from me, is not hidden from time. Each step is already known, and I am waiting for it to unfold. Walking is similar.

Bergson’s duration

Here, the philosopher Henri Bergson offers insight. Against the mechanical view of time as a series of separate moments, Bergson described real time as la durée, or duration. Bergson saw time as qualitative, continuous, and indivisible. Duration is not the ticking of a clock but the flow of consciousness in which past and present blend together and the future develops naturally.

Walking makes duration visible. Each stride is inseparable from the memory of the last and the anticipation of the next. The past, present, and future are not distinct compartments, but rather continuous. When I walk, I experience the passage of time, helping it take shape through rhythm and awareness.

Memory and becoming

Bergson also understood memory not as a fixed archive but as a living presence. The past lingers, extending into the present. Walking the uneven cobblestones of a London street dissolves the years, bringing the past into the present.

In this way, time already knows me, what I have been, and what I may yet become.

Virginia Woolf, in Mrs Dalloway, describes how moments expand and contract, and how internal time differs from external time. A single chime of Big Ben marks the passing of the day, but consciousness moves at its own rhythm, fueled by associations. Thus, time derives meaning from us and also carries us forward in its flow.

Poet’s know

T.S. Eliot, in Four Quartets, pointed to the paradox:

“Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.”

The present is never just the current moment; it includes past events and contains future possibilities. Eliot captures in poetry what Bergson proposed philosophically: time is not a simple sequence of moments but a complex weave of memory, presence, and potential.

The walking exchange

Walking turns this abstract idea into experience. The crunch of gravel, the rhythm of breath, and the shifting shadow all mark time, giving it shape. But time is working on me as I tramp along: fatigue, anticipation, and unbridled thoughts.

I help time understand what it is through my presence and measurement. And time knows what I will become, for my becoming is always already contained within its duration.

Living with duration

Philosophy reminds us that time is more than what we measure; it’s mysterious. Bergson shows us it is experienced as duration; literature and poetry show time’s texture through memory and consciousness, reminding us that all time converges in the present.

Walking means connecting with a broader sense of time beyond our daily dissections. I help time understand what it is, just as time knows what I will become.