Rethinking institutional reform, part 1: When systems fail, who has the right to fix them, and what does it cost?

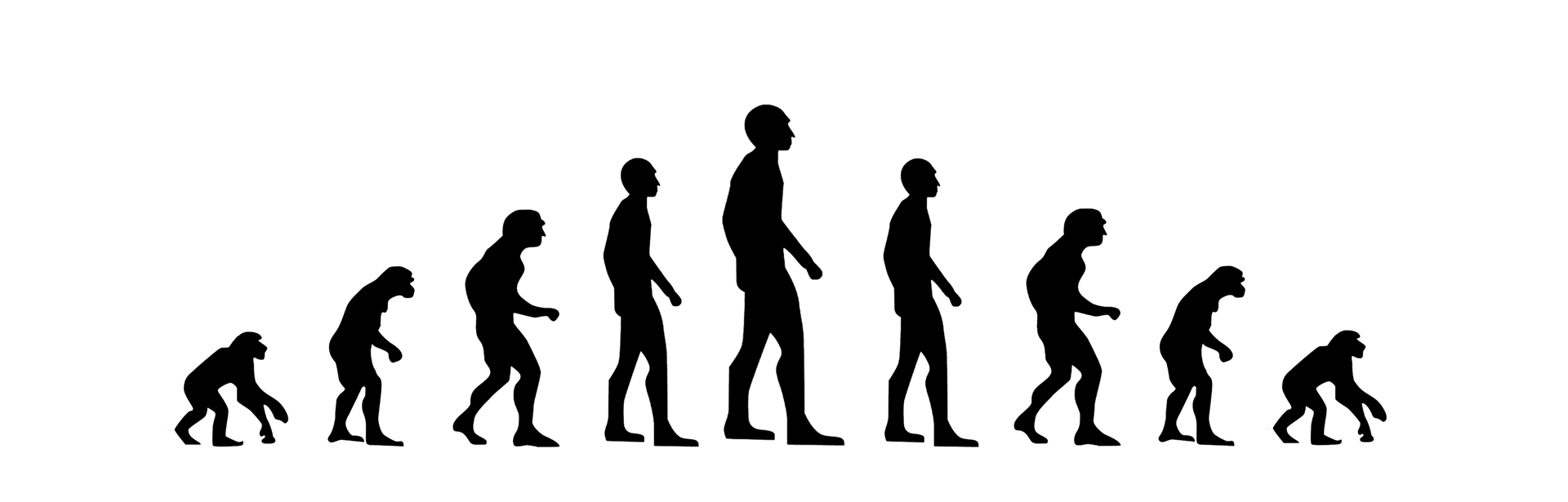

Defence says it wants evolution, not revolution. But is gradual reform enough in an era of rising strategic risk?

First published in the Mandarin

The right to reform

Technological, political, and cultural pressures are destabilising Australia’s institutions. Internally, the need for reform is recognised. However, as the Vice Chief of the Defence Force (VCDF) recently stated at the recent Defence and Industry Conference, the preference is for ‘evolution not revolution’. This phrase is commonly used by senior leaders. It signifies stability, continuity, and gradual change.

Nonetheless, the VCDF recognises that Australia’s strategic outlook has significantly shorter warning times. We also need to consider a volatile and unpredictable global political environment, increased strategic rivalry in our region, and a variety of other unforeseen scenarios. In this context, is our strategy of maintaining continuity and gradual adaptation realistic?

Defence is not alone in facing these types of institutional challenges. Australia has numerous State and Federal government agencies under pressure to respond to volatile and uncertain environments. The departments and agencies responsible for aged care, childcare, disability support, housing, energy, and more face similar pressures. Additionally, every enterprise is grappling with the pervasive and unpredictable impacts of AI and cybersecurity.

Are our public service leaders ready, not just operationally but also philosophically, to lead the response to these challenges?

This is the first article in a three-part series that explores the overlooked questions of institutional reform:

When is reform justified?

How can leaders navigate complexity and unpredictability?

Who should lead organisational change?

These articles question the ‘evolution not revolution’ approach to examining institutional change through the metaphor and ethics of revolution. They encourage public service leaders and executives to rethink the nature of leadership in reform and to challenge the comfortable language and metaphors often used in public service reform.

The right to reform

Institutional reform or transformation is often seen in technical or strategic terms. We reform to boost efficiency, foster innovation, or leverage digitisation. But rarely do senior leaders ask the question: Do we have the moral right to change this organisation in this way, at this time?

The answer is often assumed to be “Yes” due to environmental pressures, the duty of stewardship, and positional authority and power. However, reform, whether seen as evolution or revolution, is always a moral act.

Undertaking organisational reform is a deliberate and conscious decision. It has consequences, and some of these may potentially be harmful. The UK Post Office scandal and our own Royal Commissions into Robodebt and Banking illustrate the human cost of poorly managed reform.

All change and reform initiatives must be judged ethically. They can be assessed based on how well they align with moral principles such as fairness, justice, and respect.

So, for example, ERP implementation is not just a technical or business decision; for leaders, it is a moral act. Consequently, there is a need for leaders to make a compelling case for why they have the right to reform through legitimacy, not mandate.

Reform begins with moral clarity, not operational efficiency.

When is it right to change the system?

Public service leaders face mounting pressures from technological disruption, geopolitical instability, and rising social expectations. These create complex challenges for existing governance, culture, structure, and management. Yet with each call for reform, there is a parallel demand to justify the upheaval: Why this change? Why now? And who makes the decisions?

Typically, the justification is presented in technical terms, such as efficiency, digital upgrades, and alignment with strategic priorities. However, reform is not just a strategic or economic decision; it is a moral choice that alters the psychological contract between the organisation and its people.

The decision to initiate reform must undergo more scrutiny than simply having a PMO, a chart with implementation timelines, and a detailed benefits realisation package. The primary question for leaders is: do we have the right to do this?

Reform as moral action

In political philosophy, revolutions raise the most profound questions of legitimacy: When is it justifiable to overthrow a system?

Philosophers like Thomas Hobbes, Immanuel Kant, and John Locke grappled with this dilemma. All were concerned with the relationship between the State and revolution.

Hobbes argued against revolution under any circumstances; for him, order was paramount. Kant, likewise, feared the chaos of insurrection. For Hobbes and Kant, the stability and certainty of government were always preferred over the uncertainty of revolution. Locke, however, argued that when the state violates its contract with the people, revolution is not only justified, it is necessary.

Organisational reform may seem far removed from revolution against the State. However, both involve disrupting the status quo, asserting a new vision of order, and demanding a realignment of loyalties, values, and behaviour.

If we take Locke seriously, the leaders of organisational transformation must justify their right to disrupt the status quo with more than just competitive pressure. It must be based on a breach—real or imminent—of the organisation’s duty to its people or its broader mission. This reframes reform as a fundamentally moral action.

The decision to change must be judged not just by its necessity or feasibility, but by whether it upholds or undermines the implicit social contract at the heart of organisational life.

The thin justifications of business as usual

Organisational reform is often justified using vague or circular language, such as “to keep up,” “to remain competitive,” or “to modernise.” These common phrases are convenient ‘weasel words’ that rarely withstand close scrutiny.

Consider the case of ERP implementations. These projects are often seen as urgent and unavoidable, driven by vendor cycles, cloud migration, and integration needs. The technical and financial risks are significant, sometimes reaching hundreds of millions of dollars. The disruption to implementation, governance, management, and work practices, as well as the distraction from daily tasks, is equally considerable.

Implementing an ERP is one of the most important and costly decisions a senior leadership team will make. Yet, the ethical justification for implementation is rarely mentioned or assessed. Why should the organisation bear the costs, disruptions, and risks? What is being improved in organisational, human, or moral terms?

Without a moral story, reform relies on managerial directives and circular, untestable claims about efficiency. The workforce, the enablers and supposed beneficiaries of the implementation, are seen as problems to be solved rather than a group to be persuaded.

Reform as a breach of the social contract

Every organisation operates on an unspoken agreement: in exchange for effort, employees expect fairness, purpose, and a certain level of stability. Organisational reform breaches this understanding, even when it is well-meaning.

It asks people to let go of the familiar for the unfamiliar; it requires the workforce to trust that the leadership believes the change is necessary and will be implemented fairly and respectfully.

This is why organisational reform is often experienced as betrayal, even when leaders believe they are acting in the best interest of the enterprise.

The philosophical tradition of jus ad bellum (the rules governing the right to start a war) provides a useful analogy. Leaders need to be able to answer not just whether reform is technically feasible, but whether it is:

Just: Is the cause serious enough to warrant disruption?

Proportional: Will the benefits outweigh the harms?

Legitimate: Do leaders have the right to act on behalf of the whole?

Transparent: Are the reasons clearly communicated and debated?

Necessary: Are there no less disruptive alternatives?

Without such principles, reform risks becoming a form of internal imperialism, where change is imposed from above without consent or legitimacy.

From planning to persuasion

John Adams once wrote of the American Revolution: “The Revolution was in the minds of the people… before a drop of blood was shed at Lexington.” The real work of revolution, he insisted, was not the battle but the persuasion. This lesson applies equally to enterprise reform.

Most change efforts fail not because they are technically flawed but because they lack moral resonance. Leaders too often mistake planning for persuasion. Yet without the engagement of the people, even the most rational plan collapses under resistance.

To establish moral legitimacy, leaders must initiate reform with a narrative that resonates with values, not just targets. They must articulate not just a future state, but a shared purpose. And they must demonstrate that the change is not merely efficient or necessary, but right.

Reclaiming moral leadership in reform

Organisational transformation isn’t just about strategy presentations, change models, and implementation milestones. It’s a moral endeavour that reshapes identity, purpose, and working conditions. Leading reform involves claiming the authority to redefine the social contract. And that authority must be earned.

Reform, like revolution, begins in the minds of the people. Without a moral foundation, no amount of technical skill will suffice. The right to reform comes not from position, but from persuasion, principle, and the promise of something better.