The Ancient Mariner: causation and consequence

Change leadership remains unfinished until it clearly explains the cause and the consequences. Only then can the organisation understand what has occurred and why.

I. The poem as a mirror of cause and effect

Organisational life today is filled with change but lacks deeper meaning. While there are many plans, frameworks, and metrics, the underlying reasons behind events are often overlooked. We tend to see results as isolated incidents rather than as outcomes of previous causes. As a result, the understanding that human actions lead to real consequences is often forgotten.

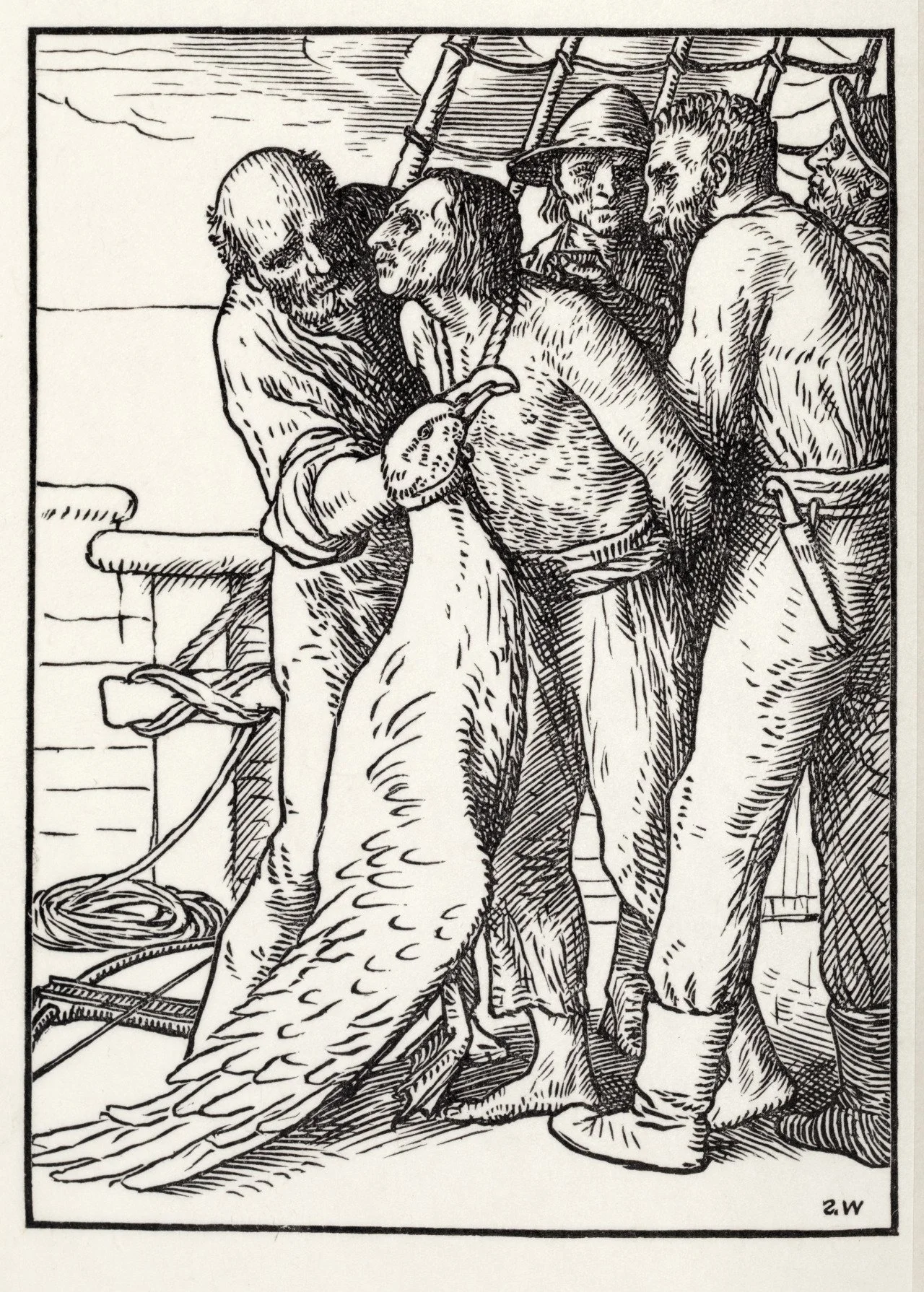

Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner endures because it is built entirely around this moral physics. An impulsive act—a sailor killing a seabird—sets off a chain of effects that expand with each stanza. The poem reminds us that change is not a “program”; it is a series of causes set in motion, each bearing a moral weight.

II. The albatross: where causation begins

The mariner kills the albatross without a reason. It is a causally blind act, disconnected from its context. Yet the world responds firmly. The wind stops. The ship stalls. The crew endures. Coleridge’s metaphysics is clear: to break the order you rely on is to unleash consequences beyond your control.

This is not punishment but consequence, and it closely aligns with how organisations function. A restructure might seem logical on paper but can damage trust. A decision made without listening can appear efficient but damages future cooperation. A metric imposed without proper context might seem objective but can erode judgement. All are causes that build up effects.

The mariner’s fate, Life-in-Death, exemplifies this moral framework. He survives not out of mercy but because of obligation. Like a figure from Greek tragedy, he is doomed to live long enough to understand the origins of his suffering. As Paul Ricoeur argued, we only grasp our own agency when we connect episodes into a clear causal chain. Until the mariner recognises his act as the initial cause, his experience remains hard to understand.

III. Recognition as the hinge of consequence

The key moment in the poem isn't strategic or procedural but perceptual. When the mariner blesses the sea-snakes ‘unaware’, he experiences what philosophers from Augustine to Iris Murdoch call a moral conversion of attention. He suddenly recognises what he had previously refused to see: the intrinsic worth of the world he had violated.

In Murdoch’s terms, the mariner’s vision clears. His false sense of importance dissolves, and he understands a reality bigger than his own will. In that moment, the albatross drops from his neck because he has finally connected cause and effect. Recognition restores the moral order.

This change isn't about acquiring new knowledge; it's about shifting our perspective. Phenomenology shows that the way the world appears changes when our attitude toward it shifts. The mariner’s redemption starts when he perceives causality not as a misfortune imposed on him, but as a sequence he caused.

IV. How consequences shape others

The wedding guest arrives as an unwilling listener, but the mariner’s testimony influences him. By the end, he leaves “a sadder and a wiser man”. What has shifted isn’t his situation but his understanding of how human lives are interconnected through causes and consequences.

Philosophically, this echoes a long-standing insight from Aristotle to MacIntyre: narrative is the way we comprehend moral action. We see our lives not as isolated events but as stories shaped by choices, failures, and their consequences. The wedding guest learns simply by witnessing a human being who has honestly traced his own chain of causation.

Hannah Arendt summarised it well: storytelling reveals meaning without needing to formalise it. The mariner does exactly this. He doesn't provide doctrine; he offers a sequence—action, consequence, recognition—and the wedding guest learns through witnessing someone who has fully lived that journey.

V. Organisational change as causation

Organisations seldom view change as a moral chain of causes. Nonetheless, every decision redistributes consequences. It shifts focus, changes relationships, and unsettles implicit agreements. These effects build up whether recognised or not.

The mariner’s drift mirrors that of organisations confused by the results they face: distrust, fatigue, disengagement. These are not mysteries; they stem from earlier causes. A decision made without relational judgment weakens cohesion. A change enforced without explanation erodes meaning. Over time, these effects accumulate into moral weather. It is an atmosphere that is hard to define but impossible to ignore.

Leading change effectively requires acting with causal awareness, anticipating both obvious results and unseen consequences. Mariners often realise this too late, but organisations can gain this insight beforehand.

VI. Leadership as testimony

By the poem’s end, the mariner has not returned to everyday life. His role shifts to telling the story of the causal chain he once ignored. He is compelled to speak so others can understand cause and effect before they make the same mistake.

This form of leadership is easily lost in contemporary practice. Leaders often concentrate on achievements or future plans but rarely recount the story of cause and effect: what their decisions set in motion, what was broken, which relationships frayed, and what lessons were learned. Yet philosophers of moral responsibility from Bernard Williams to Charles Taylor point out that acknowledgement itself is an ethical act. To honestly narrate the causal chain is to accept responsibility for its outcomes.

Change leadership remains unfinished until it clearly explains cause and consequence. Only then can the organisation understand what has occurred and why.

VII. Causality as a form of care

Coleridge does not offer a change model, but he presents something different: an ethic of attentiveness to consequences. The poem highlights that every action enters a moral sphere, and that relationships, whether within teams, systems, or the natural environment, possess causal power.

Leading with causal clarity means leading with care. Caring about the impacts of our choices. Caring for those who endure the consequences. Caring enough to be honest about the sequence we started.

Like the mariner, leaders may find that their greatest influence is not in controlling outcomes but in illuminating connections—helping others understand how actions lead to consequences, and how grasping those consequences is the start of wisdom.